This January, in support of the Toronto Rape Crisis Centre / Multicultural Women Against Rape, friends and family have raised over $1,500 (which, when matched by my employer, totals $3,000). As a result, I now have to watch and write about thirty-one horror movies: one each night. Any donors who contributed over $30 were given the option to choose one of the horror movies I must subject myself to. After each viewing, I will write some things about said movies on this website. Be forewarned that all such write-ups will contain spoilers, and many of them will refer to unpleasant and potentially triggering situations. Today’s film was selected by my very own sadistic brother, Andrew Munday. The film is Japanese found footage creep-fest, Noroi: The Curse (2005) by director Koji Shiraishi (Grotesque). I made use of my free month-long trial of horror streaming service, Shudder, which has exclusive streaming rights to Noroi: The Curse.

What happens:

Trigger warnings: suicide, abortion.

Gird your loins, friends, because we’re about to delve into the first film yet in this marathon to give me some serious chills. Noroi can be (and often is) compared positively to The Blair Witch Project. Like that earlier film, it, too, professes to be a documentary deemed too disturbing to be viewed by the general public.

Masafumi Kobayashi (Jin Muraki) is a journalist of the weird and unknown. He produces a series of VHS releases that look like a Japanese version of Unsolved Mysteries. In April 2004, after finishing a new VHS documentary, The Curse, his house burned to the ground, killing his wife. Kobayashi himself was never found. The distributors of his tape series now present his last project, The Curse, which opens with a quotation from Kobayashi himself: “I want the truth, no matter how terrifying.”

The documentary starts in Tokyo, November 2002, as Kobayashi interviews a woman who claims to hear eerie baby voices from the house next door. But there’s no baby next door; just a middle-aged woman and a boy who looks about eight. Naturally, Kobayashi tries to interview the neighbour next, but the haunted-looking woman answers the door and verbally attacks our host: “How can you talk to me this way!” The interview proves impossible. When Kobayashi plays back the videotape, he can hear the strange sounds. He takes the film to Suzuki (Hajime Suzuki), an audiologist, who determines it to be the voices of five simultaneous baby cries.

A few weeks later, the neighbour, Mikako Okui (Mikako Okui) informs Kobayashi that the neighbours left, and – with them – the weird baby noises. Kobayashi snoops around the now-vacant home and discovers the woman’s name is Junko Ishii, and the yard is mysteriously littered with dead pigeons. Days later, Ms. Okui and her daughter die; they lose control of their car and drive into oncoming traffic.

The film switches gears with an excerpt of a variety program in which Hiroshi the Psychic (Hiroshi Aramata) runs a battery of tests for ESP on ten young hopefuls. One child, Kana Yano (Rio Kanno) shows an uncanny ability, recreating a hidden drawing nine times out of ten. (The tenth time, she draws a creepy mask, which doesn’t match the drawing at all.) Miraculously, Kana also is able to telekinetically produce water in an empty jar – but that’s not all she produces. The water also contains some plankton and the hair of a newborn baby (!). (In North America, we call that Vitamin Water.)

Catching wind of this psychic girl, Kobayashi interviews Kana Yano’s parents. They note their daughter has been listless since the TV taping, though doctors find nothing wrong with her. The documentary then cuts to clip from a Ghost Hunters show, in which our hosts, The Un-Girls (Angâruzu), bring actress Marika Matsumoto (playing herself) to a supposedly haunted shrine. Marika claims to have a bit of the sixth sense. Her sense leads the trio to a spot marked by two dead trees, then she hears the low sound of a man’s voice. (The hosts do not hear this voice.) Marika turns to face something unseen, then collapses onto her back, screaming in a panic.

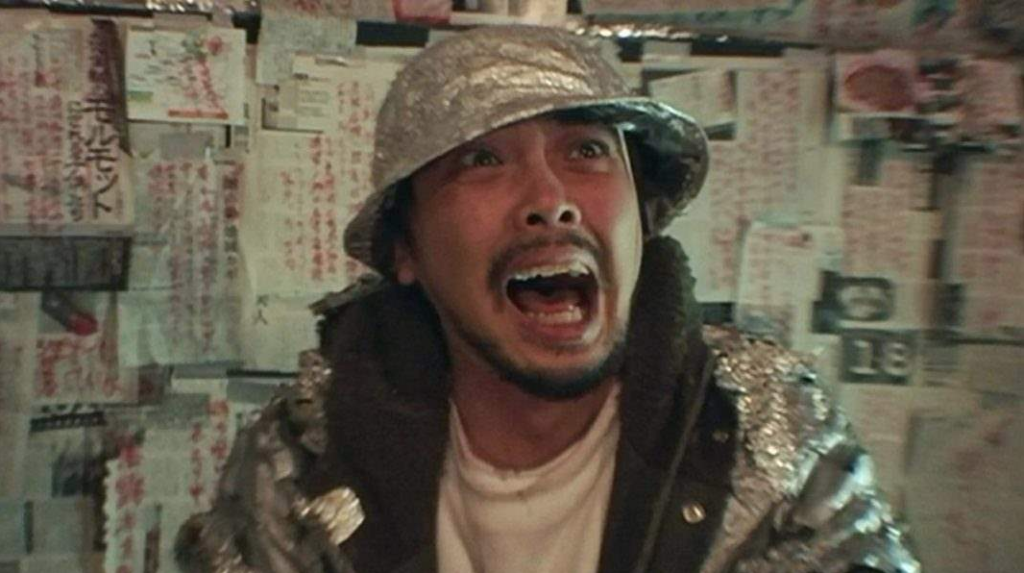

The camera pulls back, showing that this clip was part of a live stage event, “True Horror Stories,” in which the actress Marika is being interviewed about her experience in front of a crowd. Marika claims to remember nothing after she heard the voice. The event organizers have invited a special guest, super-psychic Mitsuo Hori (Satoru Jitsunashi), to meet Marika. Hori wears a tinfoil hat, tinfoil jacket, and exhibits many of the ticks and behaviours of people with severe autism. When they introduce Hori to Marika he leaps across the stage to attack her, and begins to rant about pigeons.

Our in-film host, Kobayashi, then interviews the director of the Un-Girls ghost-hunting program. He shows Kobayashi something unsettling in the unedited footage, but it’s left a mystery to viewers for the moment. Kobayashi later interviews Marika, who has started unconsciously drawing strange patterns of loops. He shows her the unedited video and pauses at the moment that startled the producer. In the distance, between two trees, you can see the distinct ghostly shape of a child. (Creep city!)

The documentary returns to the psychic child, Kana, who has started talking to herself when no one is around and making doom-laden predictions. Over dinner one night, Kana drops her spoon. The bowls and plates all slide off the table as she screams. During another variety show, an actress visits our outsider psychic, Mitsuo Hori, at his home. His garage is covered in strange written messages. Invited inside, the actress discovers the walls and surfaces are covered in aluminum foil as well as Hori’s strange fliers that warn of of ectoplasmic worms.

On December 22, Kana Yano goes missing. When Kobayashi interviews the worried parents, they note that a man in a tin foil hat started recently visiting their daughter. Kana herself told her parents the man was no threat, but she was literally an eleven-year-old girl. They show Kobayashi a flier they found in her bedroom – one warning about ectoplasmic worms and covered in strange loopy patterns. Given the evidence, Kobayashi confronts Hori at his home. It isn’t long before the psychic begins to weep openly and claim the ectoplasmic worms got her. But then, he’s struck by a premonition. He takes a sheet of blank paper and begins to sketch manically, shouting out descriptive words: “blue building, galvanized iron sheets.” He’s drawing Kana’s location! He then gestures in a direction for Kobayashi to begin his search, and stops cold. “What’s Kagutaba?” he asks, panicking. He continues to scream about “Kagutaba” as the video image breaks and is interrupted by inexplicable images of small masks.

Armed with their highly interpretive map, Kobayashi and his crew try to find a blue building. The search is cut short when the actress Marika calls him. She has been unconsciously tying yarn into very complex loops, and doesn’t know why. Kobayashi sets up a camera to document Marika’s sleep, Paranormal Activity-style. When they review the tape the next day, they hear a strange banging, and see that Marika went sleepwalking on the balcony. When they investigate the balcony, they find similarly complicated loops of yarn. They ask Marika’s upstairs neighbour, another actress, Midori Kimino (Mana Okada), if she’s heard any banging in the night. She hasn’t heard a thing.

By January, Kobayashi believes he’s found the building in Hori’s drawing; it looks nearly identical. He visits the apartment in question and can hear someone (or something) inside, but no one answers the door. So Kobyashi inquires with a neighbour who says the occupant, Shinichi Osawa (Takashi Kakizawa) is in his mid-twenties, lives alone. He’s never seen Osawa with a young girl before. Kobayashi returns again later, and they see his verandah is the only one that has attracted pigeons. That’s when the camera spots Osawa as he steps out onto the balcony, grabs a pigeon in his bare hand (gross!), and returns inside. (Strikingly, the other pigeons seem unfazed.) A few days later – you guessed it – Osawa goes missing.

Audio expert Suzuki analyzes the strange bumping sound on the Marika sleepwalking tape. When they isolate it, it seems to be a low voice saying an unusual word, “kagutaba.” It’s a word Kobayashi has only ever heard said by Mitsuo Hori, and a word that now fills me with dread. Kobayashi plays the isolated sound for Marika. She identifies it as similar to the voice she heard at the shrine, but she has no idea what the word means. Kobayashi goes to his rolodex of linguists and tries to define “kagutaba.” Eventually, he strikes gold with Professor Kazuhide Shiyoa (playing himself), who believes it comes from an old Shimokaga Village near Nagano, where the superstitious villagers used to hold a ritual to pacify a demon. The name of that demon? Patrick. (Just kidding. It’s Kagutaba) That’s when Kobayashi realizes his story may necessitate a trip to the other side of Japan.

Near Nagano, Kobayashi meets with a local historian, Toshinori Tanimura (also as himself), who describes a regular demon ritual that was held in a nearby town until 1978. After that, the valley was flooded to create a dam. Luckily, Tanimura just so happens to have a film strip of the final such demon ritual. The priest, a Mr. Ishii confronts a woman portraying the demon (with fright mask and all) Kagutaba. He bows and claps in a particular way to appease the demon, but once the ritual ends, the woman falls to the ground, shrieking as a woman possessed. Kobayashi demands to speak with the priest, but he’s dead. The woman in the film was his daughter, and supposedly lives in a nearby town. That woman’s name: Junko Ishii, the weird neighbour from the beginning of this film!

Kobayashi drives to the village community near Nagano. Houses are marked with a sickle above the threshold of their doorways, and everyone owns a dog – all old ways of the sorcerers who used to comprise the flooded village. When Kobayashi gets to Junko’s house, he finds an overwhelming quantity of looped yarn, and the now-familiar drawn patterns all over the outer walls of her building. In a reprise of the film’s opening, Junko Ishii (Tomono Kuga) again attacks the filmmakers when they approach. Neighbours warn Kobayashi to steer clear of her. An old friend of Junko’s claims she started acting strange after the last Kagutaba ritual.

To pursue a lead from Junko Ishii’s past, Kobayashi speaks with the nursing school she studied at, and the abortion clinic where she worked. They note Junko was very reserved, and only spoke about work; never about her personal life. Her former colleague notes the clinic where they worked performed “illegally late-stage” abortions, and Junko was the person in charge of disposing of the embryos. Apropos of nothing, she tells him a rumour that Junko supposedly took some of the embryos home. That’s when Marika calls Kobayashi with tragic news: Midori, her upstairs neighbour, has hanged herself. And not only that: she hanged herself with six other total strangers in a public park. One of the other suicide victims: none other than Shinichi Osawa (the pigeon-grabber himself).

Masafumi Kobayashi and his wife, Keiko (Miyoko Hanai), decide to take in a frazzled Marika. Shortly thereafter, Kobayashi learns that Osawa often fought with the other neighbour, a middle-aged woman, about the baby cries that emanated from her apartment. And shortly after that, Kana Yano’s father stabs his wife to death and turns himself in to police. Back at the Kobayashi homestead, Marika makes a fancy lunch for Keiko (“spaghetti bongole (?) with potato salad”), but Keiko is alarmed when her houseguest falls into a trance and begins to moan like an old man. Moments later, a number of pigeons crash into the sliding glass door window and Marika recovers.

Given the series of events so far, Marika is understandably spooked and fears that she’ll be the next person to die. Kobayashi takes Marika to see Mitsuo Hori. They play the tape of Junko Ishii for him and he flies into an apoplectic fit. Marika sees only one possible solution that could save her: to travel to the Shikami Dam and try to recreate the demon ritual. Kobayashi first refuses – that’s a terrible idea – but eventually relents. And they bring Mitsuo Hori along with them, because why not?

The trio grab a cameraman make the long drive to Shikami Dam. As the former village is now underwater, Kobayashi and Marika must row into the middle of the reservoir before she can do the ritual bowing and claps. Following the ceremony, she feels better – stronger. But back on shore, Mitsuo Hori begs to differ. He is flipping out, demanding they paddle back. He insists they drive off the mountain and go home, but moments after runs deep into the woods, shouting “Kana, Kana!” Kobayashi grabs a camera and follows him, while the cameraman and Marika return to the car and drive back as night quickly descends.

Marika, obviously, is not actually better. She falls asleep in the rear of the car and soon begins to moan. When the cameraman stops the car, she makes a run for it, eventually looking up to the sky, falling, and screaming as if attacked. Mitsuo Hori, meanwhile, has led Kobayashi deep into the dark woods, where they begin to find dead dogs in every direction. Eventually they find a roped-in perimeter, piled high with dead animals, and an ancient shrine. The forest goes completely dark, and Hori screams more frantically than ever. In the camera’s night-vision mode, you can see grainy footage of what looks like a woman or girl, covered with wriggling babies. Moments later, it’s gone, and – on the other side of the mountain – Marika snaps out of her episode.

Kobayashi and his cameraman bring both Hori and Marika to a hospital, but return to Junko Ishii’s house. Like a Japanese Fox Mulder or Geraldo, Kobayashi breaks into Ishii’s house when there’s no answer – the truth is in there! – only to discover refuse and dead pigeons everywhere. Most disturbing of all, he finds Junko Ishii’s body hanging from a noose. But that’s not all. When they step further into the room, they find a shrine of sorts piled high with Kagutaba masks, dead pigeons, and looped yarn. And behind an altar: Ishii’s young boy crouched over the dead body of Kana Yano.

We learn that the boy, thought to be Junko Ishii’s son, was not related to him. The Kobayashis adopt the traumatized boy, who barely speaks. We later learn that Marika returns to her work on television, but Hori, unfortunately, has been institutionalized and is allowed no visitors. That’s when the historian, Tanimura, calls Kobayashi again. All the Kagutaba reminiscing led him to go through his old stuff, and he found a tapestry in his grandfather’s collection. The fabric outlines the ritual to summon Kagutaba: villagers sacrificed baby monkeys and offered them as food to a medium (a psychic like Kana Yano). That’s when Kobayashi makes a horrifying revelation: that’s how Junko Ishii must have been using Kana Yano – to summon Kagutaba. Kana Yano was that girl, briefly glimpsed, covered in writhing infants. But now she’s dead, right?

That’s where Kobayashi’s film ends. But the film about the film isn’t done with. As mentioned, the Kobayashis’ house burned down shortly after the video was finished, with Keiko dying in the fire, and Masafumi vanishing. Mitsuo Hori, we are informed, later escaped his institution and was found dead in an apartment’s air duct. One month after the fire, the Sugishobou Video Publishing company receive a mysterious package from Masafumi Kobayashi: a video camera with a cassette tape still inside. The company plays the tape and – guys – it’s just the worst, scariest thing.

If you thought the girl crawling with babies was unsettling, wait until you see Noroi’s hideous but bravura final long take. The tape shows the Kobayashis awakened by an escaped (and agitated) Mitsuo Hori. Dressed in a robe and holding a rock, he claims “Kagutaba lives!” He sees the child they’ve adopted and threatens him with a rock. “Kagutaba!” Kobayashi, like any good Offspring fan, keeps them separated, but Hori overpowers him and bashes the boy’s head in with a rock. The camera turns away from the bludgeoning, but it turns back to even worse horror. A docile Hori now stands behind the child, who is standing upright and stock still, his head crushed and bleeding. Keiko falls into a trance and begins to moan. Hori walks up to Kobayashi (holding the camera) and smacks him with the rock, then leaves with the eerie child. Immediately after, Keiko goes to the kitchen, douses herself in gasoline, and lights a match.

Takeaway points:

- I’d be willing to rank Noroi: The Curse as the scariest film I’ve yet watched this January. Found-footage horror can be a real mixed bag, but Noroi is exceptional for a few principal reasons. For one, in much the same way Unsolved Mysteries creeped out television viewers, this film doesn’t rely on jump-scares or hidden images. Though there are some particularly memorable scenes, it’s more that every moment of this film is unsettling from frame one. And two, it feels like a documentary film – it’s not just grainy footage, but a package put together of clips from live events, faithfully recreated segments from variety shows and reality TV. The pieces assemble to make what seems, in many ways, like the real deal. And, finally Noroi makes great use of the long take. I’ve already said enough about how effectively disturbing the long final shot is – it’s a moment you truly wish you could un-see – but there are a number of other scenes that become creepier the longer they go without an edit.

- The flooding of a traditional Japanese village to make way for a dam serves as the catalyst for the return of Kagutaba, which makes Noroi a gentle (though terrifying) screed against the prioritization of development and modernity over the old ways. Of course, the old ways in this film seem pretty spooky themselves. But at least pre-1978, the only things that were harmed were baby monkeys and dogs.

- And what are we to make of the film’s epigraph? Kobayashi wants the truth, no matter how horrifying. In addition to the message that modernization may unleash unforeseen monsters, Noroi also suggests that an obsessive quest for the truth will only lead to madness. This is a common theme in horror literature and film, but rarely so vivid and horrifying as it’s depicted in the movie’s final scene.

- The setting of Nagano is interesting. I didn’t know much about the city or region, outside of its renown as a site of the Winter Olympics (just around the corner!). The Nagano depicted in Noroi looks a lot like one of many northern Canadian towns: somewhat remote, dogs tied up outdoors, amenities and wealth in short supply.

- Among the many confusing plot threads is the lingering one about the illegal late-stage abortion clinic, and the nefarious Junko Ishii’s possible theft fetal matter, which she (maybe?) feeds it to Kana Yano. (I was confused.) I’m still not sure how I feel about it. Are the filmmakers implicating abortion in the demonic evil of Kagutaba? And if so … what?!

- Relatedly, so many of the events (and deaths) in this movie are instigated by a neighbour complaining about crying babies. But, like, who complains to their neighbour about a crying baby? It’s a baby. That’s what it does: cries. It’s not like they have a neighbour who blasts dubstep at three in the morning. Sure, the woman didn’t live with a baby, so there’s that. But all those homeowners and tenants could just as easily have moved in beside new parents. Buy some ear plugs and grit your teeth through the baby sounds and you’ll avoid being murdered by Kagutaba. Seems simple enough to me.

Truly terrifying or truly terrible?: If you don’t like being scared, do not watch Noroi: The Curse. That is one unsettling film. I’ve given myself goosebumps several times just summarizing the plot. And that final scene should give me nightmares for weeks. The plot doesn’t entirely make sense, and it’s probably about a half-hour too long (and too complicated), but it’s honestly quite scary. This is one creepy movie.

Best outfit: For the distinctive and bold choice of using aluminum foil to create a look that’s half silver street performer and half lead singer from Wheatus, we salute you, Mitsuo Hori.

Best line: “I guess it’s too late for all of us.” – Kana Yano, answering an innocuous question, but also encapsulating the current zeitgeist

Best kill: Kobayashi’s wife Keiko setting herself on fire is the only death we see on screen, but it’s a doozy. It’s magical, the things stunt people can do with fire these days.

Unexpected cameo: Half the actors and actresses are playing themselves in Noroi. Not being overly familiar with Japanese film and television, I couldn’t tell if these mysterious IMDb credits were an attempt by the filmmakers to further mystify the film’s production and give the documentary credibility as “real,” or if the movie is like a found-footage horror version of The Trip films, with actors playing heightened versions of themselves.

Unexpected lesson learned: Despite the taste-makers, you can pair pasta with a side dish of potato salad.

Most suitable band name derived from the movie: Is there a more metal band name than Kagutaba?

Next up: Event Horizon (1997).