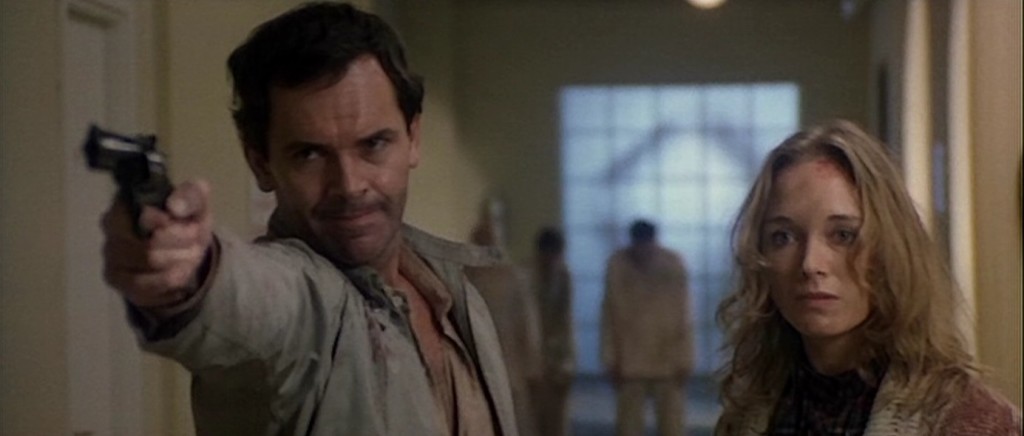

Jerry Blake, needing a little work on his poker face.

This January, in support of the Toronto Rape Crisis Centre / Multicultural Women Against Rape, friends and family have raised over $1,000, which means I have to watch and write about thirty-one horror movies. I’ll watch (on average) one movie a night, many of them requested by donors, after which I’ll write some things about said movies on this website. Be forewarned that all such write-ups will contain spoilers! The penultimate movie in my January screenings is The Stepfather, directed by Joseph Ruben (Breaking Away, Sleeping with the Enemy, The Good Son). This was the final “free space” film of the viewings, and one I watched mainly due to the presence of one of my favourite character actors, Terry O’Quinn (John Locke himself!). The Stepfather was rented from Queen Video.

What happens:

Much like It Follows, The Stepfather opens on a suburban American street, though with much larger houses than that other film. A bearded man in a washroom removes his glasses and bloodstained clothing, stripping down naked. After showering, he shaves and puts in new contacts, then puts on a nice suit. As he appraises himself in the mirror, the man is revealed to be actor Terry O’Quinn. Leaving the washroom, he places a child’s toy into the proper storage box, then walks downstairs past a scene of utter carnage in the front room. An entire family has been murdered – even a little child with a teddy bear is drenched in blood. The man opens the front door, picks up the morning newspaper, and strolls whistling down the street. He boards a ferry and as soon as it enters open waters, he shoves his suitcase into the drink.

Jerry Blake, fresh from a Jaws-themed costume party, I can only assume.

The film moves forward one year. In Oakridge, Washington, sixteen-year-old Stephanie Main (Jill Schoelen) bikes her way back to her large house. In the backyard, her mother, Susan (Shelley Hack), has been raking leaves. The two of them playfully engage in a leaf fight until Jerry Blake (Terry O’Quinn) arrives home. Jerry is Stephanie’s new stepfather (hey, that’s the name of this film!), and he greets his wife with a big sloppy kiss. He also has a surprise for Stephanie: he’s bought her a puppy. As Stephanie scratches the new dog behind his ears, Jerry pets the girl’s arm, saying, “That’s my girl.” Stephanie blanches and backs away. (I’m right there with you, Steph.)

Once Stephanie runs inside, Jerry worries aloud to Susan that Stephanie might think he’s trying to buy her love with the puppy. Susan reassures him that’s not the case. “The puppy was perfect,” she says. “You’re perfect.” Stephanie, wearing a sheep-patterned sweater, visits her therapist, Dr. Bondurant (Charles Lanyer), while Jerry Blake leans against his car in the parking lot outside. Pacing the room like a caged jaguar, Stephanie expresses her baseless (?) fears of her new stepfather. Dr. Bondurant worries because Stephanie has been acting out in school ever since her biological father died a year ago. She’s racked up a number of suspensions in just a short amount of time. During the car ride home, Jerry suggests to his stepdaughter that they both make an effort to try to get along better, and that she make an effort to do better in school. As soon as she agrees, the film cuts to Stephanie and another girl battling each other in art class. The other students jeer until a teacher breaks up the fight and sends Stephanie to the principal’s office.

We next see Jerry Blake on the job with American Eagle Realty. He shows a house to a couple with a young daughter. Jerry pushes the girl on the swing set in the backyard and tells her about his “daughter,” Stephanie, who goes to high school. When the girl says she’s in the third grade, Jerry muses, “I remember when Jill was in third grade,” and the girl catches his inconsistency. Jerry later arrives home to find Stephanie (not Jill) has been expelled from school. At first, he’s in disbelief – “Girls don’t get expelled.” – but then he’s disappointed. Stephanie suggests that boarding school is an option, but Jerry won’t hear of it. He believes boarding school would divide the family: “It’s not a family without children.” Later on, Stephanie speaks with her friend Karen (Robyn Stevan) on the phone and describes her stepfather, “Scary Jerry,” and his obsession with being like the perfect families you see on television. (Interestingly enough, we next see Jerry enjoying an episode of Mr. Ed.) Susan enters and she and her daughter have a heart-to-heart about the loss of her dad. She pleads for Stephanie to give Jerry “a chance.”

Susan retires to her bedroom, where she and Jerry promptly get down to business. Sex business. Stephanie, in the next room, puts on her headphones, cranks the Pat Benatar (or reasonable facsimile), and sighs heavily. Meanwhile, in Seattle, Jim Ogilvie (Stephen Shellen) drives reporter Al Brennan (Stephen E. Miller) in his old jalopy to the house where we saw Jerry Blake murder an entire family in the film’s introduction. Though according to Ogilvie, a “Mr. Morrison” murdered his whole family in this house. Brennan wrote the story a year ago for the Seattle Examiner. Jim Ogilvie reveals that Mrs. Morrison, the murdered wife, was his sister, and he is on the hunt for her murderous husband. Ogilvie has some evidence that Morrison couldn’t have moved too far away from Seattle, so he asks Brennan to run a follow-up story one year later, along with a photo of Morrison, in the hopes a Seattle Examiner reader will recognize him.

“I’m going to miss you gals when you’re dead.” “Wait, what?”

Jerry Blake hosts a backyard barbecue for the first five families he sold houses to in Oakridge. Jerry makes.an impassioned speech about the importance of tradition and family, and poses for a photo op with his wife and stepdaughter – an awkward moment that Stephanie can’t escape fast enough. Later, the assembled dads read a newspaper article about the Morrison murders (though it features no photograph of the killer). Blake plays dumb, asking what the murders were about, and the dads fill him in on a stepfather who butchered his entire family with knives. Jerry seems deeply affected by this news, but also concludes that “maybe they disappointed him.” (So he’s not 100% nailing this “not a murderer” act.) He takes the newspaper and folds it into a pirate hat for a neighbourhood kid. Stephanie, in the basement to find some ice cream, is startled when Jerry storms downstairs for a rage freakout, shouting “We are going to keep this family together!” When he notices his stepdaughter, Jerry explains that as a salesman he builds up a lot of stress and occasionally needs to let off some steam. (Seems reasonable.)

Post-party, Stephanie finds the discarded newspaper hat and begins to wonder if family-slayer Mr. Morrison is the same person as her unusually angry stepfather. She presents this idea to Karen, who is very dismissive. Nevertheless, Stephanie sends a letter to the Seattle Examiner requesting a photo of the murderous Morrison, as she is doing a social studies project on mass murderers. (We all remember that social studies unit.) < /p>

Speaking of photographs, Ogilvie is very upset that Brennan didn’t run one with his article. He finds Brennan and throws him up against the hood of his car. Brennan explains that, as a reporter, including the photo wasn’t his decision. Ogilvie plans his next move, obsessed with finding his sister’s killer – he’s a bit like Fox Mulder in that regard – and Brennan advises him to forget it. Ogilvie can’t forget, though: “You saw what he did them. Could you?” Stephanie floats the idea of boarding school by her therapist, who thinks it’s a fairly good idea. “What’s wrong with running away?” Bondurant asks. He thinks it will provide her and her family some much-needed breathing room. Stephanie, now clad in a unicorn / checkerboard shirt, notes that Jerry opposes the boarding school idea, so Dr. Bondurant offers to speak to him to try to persuade him otherwise. Jerry, meanwhile, has just opened the mailbox to find a letter for Stephanie Main with the Seattle Examiner as return address. He opens the letter to see a glossy headshot of himself (with full beard).

When Stephanie arrives at home, Jerry only passes her the new issue of Cosmopolitan and says nothing of the letter from the Examiner. However, all is not well. Jerry moves to his basement workshop – where he works on crafting birdhouses – and paces the room frantically while examining the photograph and mumbling about his “good little girl.” He picks up a screwdriver and knife from his tool bench, stabbing invisible enemies in mime. Only his wife’s call for dinner seems to snap him back into character as family man, Jerry Blake. The telephone rings and Susan answers. She calls down for Jerry, saying that Stephanie’s therapist wants to speak to him, but Jerry refuses to take the phone.

Back in Seattle, Ogilvie meets with Lt. Wall (Blu Mankuma) of the police and asks him about Henry Morrison. The detective confirms that Morrison was just an alias, and that he suspects the killer will strike another family before long. However, Morrison was clever and left no trace of where he might go. Wall further advises Ogilvie that if he were in his situation, he’d “get a gun and blow the sonuvabitch away.” That very sonuvabitch then visits Stephanie’s old principal and – using a bit of the old Jerry Blake charm – convinces her to reinstate Stephanie in public school. Stephanie confesses to her therapist that Jerry scares her, so Dr. Bondurant takes drastic measures. He calls Blake under false pretences, pretending to be a homebuyer seeking to view a house, to set up an in-person meeting.

On her first day back in school, Stephanie is walked home by Paul Baker (Jeff Schultz), who compliments her artistic skills. They joke and wrestle and almost kiss. Clearly some sort of romance is blossoming for young Stephanie. When Stephanie returns home, she finds an envelope from the Seattle Examiner, but the photo inside is someone she’s never seen before. (Namely because Jerry went to a photo studio and replaced the headshot.) Bondurant arrives for “Ray Martin”’s meeting with Jerry Blake, who proceeds to show him a house under renovation. Bondurant, when asked if he’s a family man, says he’s a “confirmed bachelor” (which I don’t think the makers of this film realized was code for gay). This displeases Jerry: “House like this should really have a family in it.” Bondurant also says he’s in “stress management,” then asks Jerry Blake a bunch of questions about himself. Jerry, becoming suspicious, asks, “Are you interested in buying a house or in me?” Soon after, Jerry catches Bondurant in an obvious lie – he refers to his wife, even though he mentioned he was a bachelor – so Jerry beats him to death with a stray two-by-four. Standing over Bondurant’s broken body, he shouts, “We need a little order around here!”

Dr. Bondurant was a sacrifice the island demanded.

Jerry goes through the dead man’s wallet and realizes who he really was. Methodically, he wraps him and murder weapon in craft paper, puts him in the trunk of his own car, then drives that car to the edge of a cliff. Jerry puts the dead man behind the wheel of his car, then shoves a makeshift wick into the gas tank. When he drives it off the cliff, the car explodes into flame. Stephanie is hard at work on her bicycle in the garage when Jerry arrives home to deliver the bad news: Dr. Bondurant was in a car accident and has died. “He was my friend,” Stephanie cries. Jerry hugs his stepdaughter and nods. “In his own way, he brought us together.”

Ogilvie returns to the Morrison murder house to search for any clues he may have missed. In a basement workshop eerily similar to the workshop Jerry Blake uses to make birdhouses, Ogilvie finds a copy of Travel & Leisure with several pages cut out. Ogilvie rushes to the public library, barreling through it like he’s on an episode of Supermarket Sweep. He finds the copy of Travel & Leisure with the other periodicals and realizes the missing section is a story on the best towns in America to raise families. One of them is Oakridge, Washington, not that far from Seattle. Jerry, meanwhile, finishes his latest birdhouse, and Stephanie offers to help him erect it in the front yard. She attempts to reconnect, apologizing for the way she’s been acting. Jerry accepts her apology, noting that he had a difficult time growing up, as well, though he refuses to speak further about his mysterious past.

Over Thanksgiving dinner, Jerry gets all weepy about how warmly the family has accepted him, and Susan wears an outfit more apropos of the Victorian era than 1987. Stephanie later goes for a few sodas at the local teen hangout. She leaves and her classmate, Paul Baker, rolls up on a moped and offers her a ride home. “Only if I get to drive,” she agrees. On the moped ride he wins over his beloved, mainly by insulting other girls. “Cathy Lombardo is a stuck-up bitch,” he says of his ex-girlfriend. (Who wouldn’t want to date this guy?) On Stephanie’s front step, the two kiss, but are interrupted by one very angry stepdad. “You!” he shouts. “You could go to jail! This girl is sixteen years old!” Baker protests, “So am I!” But Jerry doesn’t care. He claims Baker was attempting to rape Stephanie and scares him off. Susan comes downstairs to see what’s happening, and Stephanie complains to her about Jerry. “He’s not my father,” she shouts. “He’s just some crazy creep. How can you even bear to let him touch you?!” Susan slaps Stephanie, who runs off into the night.

It’s a bit more threatening to argue curfew with man who’s just brained your therapist with a block of wood.

However, Susan isn’t happy with Jerry either, and claims that his overprotective actions have damaged any progress she’d made in bonding with her daughter. Something sprigs inside Jerry and his eyes pop manically. The next day, Jerry quits from American Eagle Realty and says his goodbyes to his coworkers. Ogilvie presents his case to a detective in Oakridge, explaining that he merely needs access to marriage licences issued in the past year to find the assumed name a murderer has taken. The detective, believing this to be a cockamamie fabrication, refuses. But the overly handsome Ogilvie is able to charm the clerk, Ms. Barnes (Gillian Barber), into helping him in his quest. A day or so later, Susan drops Stephanie off for an appointment with a new therapist. Stephanie decides she can’t start things over with someone new, and instead sneaks into Bondurant’s unoccupied office. (The two therapists are in the same building.) Stephanie discovers an intriguing message on his desk notepad – one that seems to detail the location and timing of a meeting with “J. Blake.”

Ogilvie begins canvassing Oakridge, going door-to-door to meet all the recent husbands in town to see if they look like his former brother-in-law. Jerry, meanwhile, has boarded another ferry. In the washroom, he removes his contacts, dons new glasses, and takes off his (convincing) hairpiece, revealing male pattern baldness underneath. With his new look, he attends a job interview for insurance sales in Rosedale, Washington, under a new name: Bill Hodgkins.

Jerry (or Bill or Henry or whoever) goes for a little constitutional, during which he spies one of his client families moving into their new home. Seeing an actual happy family, devoid of any murderous tendencies, he looks sorrowful. Ogilvie visits the Blake residence, but Jerry’s not home. Susan mentions he’s out showing homes to clients. Which is not entirely the truth, as Jerry is, in fact, looking at houses in Rosedale, and, as Bill Hodgkins, introducing himself to the local single moms. (He acts fast!) Susan calls into Jerry’s work to let him know someone came calling for him, but American Eagle Realty says that Jerry no longer works there. He quit a few days ago. Ogilvie, meanwhile, visits another couple on his list of newlyweds. Trouble in paradise abounds as the young couple yell at each other, on the verge of a separation. However, they take time out of their domestic quarrel to look at Ogilvie’s photograph of Morrison. They note the beard doesn’t fit, but he looks a lot like the guy who sold them this house.

When Jerry returns home, whistling “Camptown Races,” Susan confronts him: why didn’t he tell her he quit his job? Jerry insists he still works at the realtors, and that the incompetent new receptionist must have been confused. “How hard a name to remember is Hodgkins?” he asks, not realizing he’s jumped one identity ahead. Susan is confused, especially when Jerry seems lost after his mistake, asking himself, “Who am I here?” (A phrase featured prominently on the film poster and on the trailer.) Susan reminds him his name is Jerry Blake, and Jerry thanks her by smashing her across the face with a telephone. Jerry then chokes his bleeding wife and tosses her into the basement. He returns to the kitchen, sorting through the knives, then calls the family dog to him. When Stephanie arrives, he’s playing with the dog on the floor of the kitchen, a large butcher knife in one hand. Hearing his stepdaughter arrive, he growls, “You’re a very bad girl.”

Unaware that her stepfather has shown his true colours, Stephanie takes a shower. Jerry stalks up the stairs toward the washroom. At the very same moment, Ogilvie speeds toward their house in his old beater, waylaid by a nun and Catholic students crossing the road. When he finally arrives, he lets himself in. Jerry is hiding behind the door, and is surprised to see someone he knows from a lifetime ago: his former brother-in-law, Jim Ogilvie. Ogilvie notices Jerry is spattered with blood and reaches for the gun in his pocket, but the stepfather is too quick, and stabs him in the stomach before he can fire. Meanwhile, Stephanie completes her shower and dresses. Jerry finds her in the upstairs hallway, and lunges at her with the knife. She screams and locks herself in the bathroom.

As her stepfather pounds on the door, breaking the mirror hanging on the inside, Stephanie desperately looks for a means of escape. Instead, she picks up a shard of broken mirror with a towel, so when Jerry eventually smashes through the door and mirror, she stabs him in the shoulder and flees. Stephanie makes a break for the attic, but Jerry grabs her ankle and nearly manages to drag her down. But instead, he has to follow her up into the attic. He chases her around, then falls through a weak spot in the floor, plummeting through the insulation and hitting the second floor below.

Stephanie attempts to sneak out of the house, but sees her wounded mom crawling up the stairs. Jerry revives and knocks Stephanie to the ground, but Susan has taken the dead Ogilvie’s gun and shoots her husband the back. He tumbles down the stairs, but staggers back up. Susan shoots him again, in the butt cheek, but still, he crawls to the second floor. At the ledge, he and Stephanie struggle for the butcher knife, but the daughter prevails and stabs her stepfather in the heart. His final words are “I love you.” Following the harrowing ordeal, Stephanie saws down the birdhouse Jerry built, and her mother embraces her. Both women return to the house.

When your stepfather objects to being treated like a human knife block.

Takeaway points:

- The Stepfather is nearly a fairy tale in its grim(m) depiction of evil stepfathers. (Yes, typically evil stepmothers are featured in fairy tales, but I’m sure there must be at least one or two stepfathers in all of European folklore.) Stephanie expresses the fears of many children whose parents remarry – that the new parent will be awful in comparison to her biological father. In this case, she’s completely right: not only is he awful, he’s legitimately homicidal. With divorce rates on a steady incline throughout the 1980s, this would have been a very relevant fear. In fact, the movie itself is loosely based on the story of a man named John List, who killed his family in 1971 and remained on the lam until two years after this movie was released. (Though unlike the stepfather in the film, List was the biological father to three children. Three children whom he killed – along with his wife and mother – then disappeared.)

- In addition to serving as a realization of millions of stepchildren’s fears of their step-parents, the movie is also a prescient warning that those people who seem like the perfect fathers, the perfect husbands – who quite overtly aim to make that “goodness” their identity – may not be who they seem. I hate to bring up the spectre of Bill Cosby again, but this was a comedian who built a career of being the understanding dad, who – both in his television shows and speaking engagements – called for a return to more traditional values of family and respect. He even dressed somewhat similar to the stepfather in this film. And yet, lurking under the surface was a man capable of (allegedly) raping countless women. A colourful sweater can hide a black heart.

- Director Joseph Ruben has made quite a name for himself making thrillers that turn intimate violence into riveting entertainment. Not only did he exaggerate a tale of domestic abuse to the nth degree for The Stepfather, he revisited a similar concept in Sleeping with the Enemy, and looked at the idea of an evil child (or brother) in The Good Son. Ruben seems to specialize in exploiting fears we have of our closest family members. Fears that crime statistics demonstrate are not unfounded. Ruben takes the very real violence between loved ones and ramps it up into potboiler thrillers.

- The Stepfather improbably spawned two sequels, and while only one of them features Terry O’Quinn, both of them feature the same stepfather character, who somehow survived being shot twice and stabbed in the heart to torment other unsuspecting families in the later movies. His will to create a perfect, Father Knows Best family is stronger than mortal wounds.

- I appreciated the subversion seen in the depiction of Jim Ogilvie. Throughout the film, he is set up as the lone crusader – the one person who knows what Jerry Blake is – and – as we seem him race toward a crisis situation in his dilapidated vehicle – the hero who will save Stephanie and her mother. But despite that, he’s unceremoniously murdered by the villain. Like Samuel Jackson eaten by the shark in Deep Blue Sea. His story builds, but his revenge is thwarted by a man with a knife just a little bit faster than him. This turnabout is stellar; a much weaker film would have had Ogilvie save the day, but in The Stepfather, Stephanie and mother, like the sisters in the song, are doing it for themselves.

- Not an important question, but did anybody else find it strange that the family has a taxidermied roadrunner in their dining room?

Truly terrifying or truly terrible?: The Stepfather is not great cinema. Instead, it’s a tight, trashy little thriller that rises above its station, thanks to some solid directing and great acting, especially from O’Quinn. The movie certainly has a palpable sense of realistic menace. Not the scariest thing you’ll ever see, but certainly worth watching.

When you can’t decide between a sweater vest and suit jacket? Why not wear both?

Best outfit: That’s a difficult decision because, for the most part, The Stepfather looks like it was costumed by Northern Reflections. While Stephanie Main has some nice graphic sweaters and shirts featuring sheep and unicorns (just to name some of the standouts), Jerry Blake’s wardrobe, clearly inspired by Mr. Rogers, is the real standout. His clothing adheres to a black, white, gray, and red colour scheme (which probably has some deeper meaning), and he looks like a television father at every moment. The best look is when he pairs an argyle sweater with a full suit and tie.

Best line: “Next time, Jim, call before you stop by.” – Jerry Blake, with a pretty good one-liner to the corpse of his one-time brother-in-law

Best kill: Jerry Blake beating the therapist to death with a two-by-four is pretty vicious. All the more so because Jerry literally has no idea who the man is before he kills him. All he knows is that he threatens the carefully constructed house of lies he has built.

Unexpected cameo: Blu Mankuma, who plays Lt. Wall, has been in almost every movie and television show made in the past few decades. (He was even in an episode of Danger Bay!) Most notably, he was a recurring character on 21 Jump Street, even appearing in the pilot episode.

Unexpected lesson(s) learned: Never trust a man who builds birdhouses as a hobby. Avoid marriage to someone if they have no friends or family that they’ve known for over a year.

Most suitable band name derived from the movie: American Eagle Realty

Next up (and last!): The Beyond (1981).